By Melanie Medina

The most vivid memory I have of my Uncle Jim was when my cousin Katy and I were in the back seat of his car singing, Little Bunny Foo Foo, I don’t wanna see you pickin’ up the field mice and boppin’ ‘em on the head.

We were doing the hand motions and everything. Scoop-and-hold motion with the left hand, boppin’ the pretend field mouse with the right.

Uncle Jim made us stop singing the song because it was such a cruel way to treat a field mouse.

I can’t say that I knew my Uncle Jim very well. It seemed to me that he got grumpy easily and would then want to be by himself. Besides that, what I remember about my uncle: he loved animals, and he had enormous amounts of empathy for anyone who was hurting.

When I was going through some orthodontic work as a teenager, he showed me that if I clenched my jaw together and put some pressure on my molars—not too hard—it would give me a bit of relief, or rather it would change the type of pain that I felt, which in a way is relieving, I suppose.

Also—and this is pretty important—he introduced my dad to my mother in the 1970s, so if it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t be writing this.

I also know that when the Gulf War started, he began to suffer flashbacks to his time in the Vietnam War.

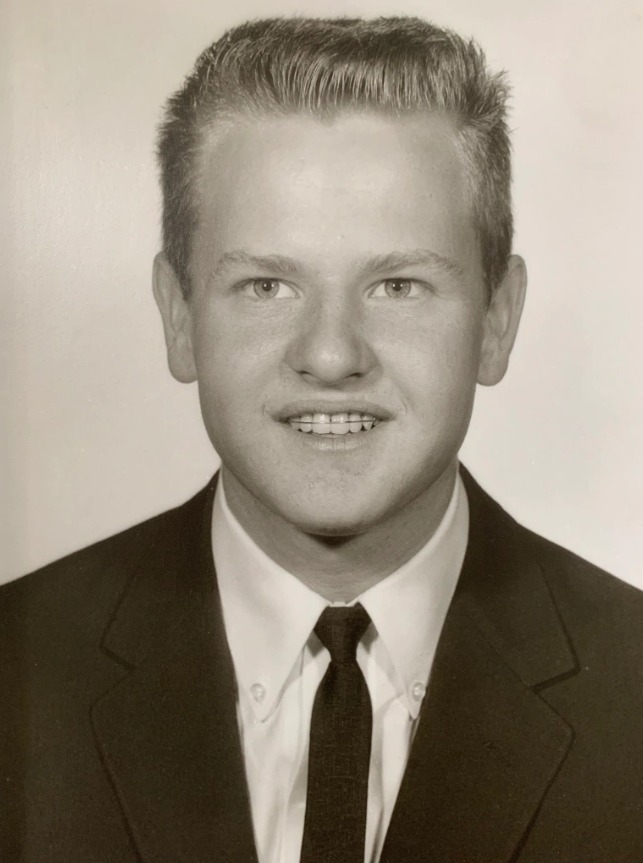

He was inducted into the Army in January 1967 at just barely 19 years old.

He was stationed somewhere in the central highland region of South Vietnam. His combat tour ended at about 9:30 a.m. October 19, 1967, when his helicopter came under enemy fire, which caused it to crash.

“I was one of several soldiers on that craft that was seriously injured and was sent back to The States for medical treatment,” he wrote in a letter to his grandson, which Katy shared with me.

In that letter, he also described a picture that someone had taken of him in a Vietnam village off the coast of the South China Sea.

“I am giving this woman some antibiotic ointment to rub on some sores on her baby’s head,” my uncle wrote. “We had found the ointment in a stash of supplies we came across when we destroyed a Viet Cong bunker a couple of days before.

“I don’t know if it helped the baby but it just seemed like the right thing to do.”

I imagine that destroying a bunker—when it’s not in your nature to fathom even a field mouse being hurt—does something to you. It did something to my Uncle Jim.

He came back home with his jaw in pieces. He hid his scars under a beard until the day he died.

When one of the nurses who took care of him in his last days told me she was going to shave his beard, I asked her if she wouldn’t mind just trimming it instead. When she let me Facetime with him two days before he died, I was so happy to see his clean and neatly trimmed beard.

The beard was good for hiding most of his scars, except for the one on his cheek that I had always believed to be a dimple. It wasn’t.

The beard did a terrible job of hiding his emotional scars. Everyone close to him could see he was fighting internal demons. They seemed ruthless and relentless. Even a kid could sense his pain.

My uncle is finally at peace. He died on Sunday, March 28, 2021, of cancer. He so kept to himself that, according to what the doctors tell us, once he learned he had some type of cancer, he did not go back to find out what type. At one time, we heard it was mesothelioma. But he used to smoke a pipe, so maybe it was smoking-related lung cancer.

My cousin had him cremated. Last weekend she arranged a military service for him at Texas State Veterans Cemetery at Abilene, and it was absolutely beautiful.

I’m humbled by his service and sacrifice. He deserved the honor of a veteran’s service.

At the end of it, a woman who worked at the cemetery poured out some of his ashes over the scattering garden.

When it was over, Katy and I and our families drove to Seymour. It’s a tiny town halfway between Dallas and Lubbock where my dad and Uncle Jim lived from the time they were 10 and 8 years old, respectively, until my dad left for college at University of North Texas in Denton, with Jim following behind him two years later.

Based on what family have told me, my uncle joined the Army as a form of rebellion against my grandparents.

Katy and I went to the Seymour rodeo and watched barrel racers and bull riders, just like our dads did in the 1950s and ’60s.

We fed our kids Frito pie and nachos and watched the sun set behind the bull pens.

As we walked back to our cars, we cut over to one side in the grass. Out of my purse, I pulled a tiny urn that held some of my dad’s ashes. She opened a black box and pulled out a bag of the ashes she’d saved from her dad’s service. We poured them out and let the breeze mix the ashes of our dads together. We watched them settle in a little field in the town where they grew up.

I don’t know if resting in peace forever in the grass near the Seymour rodeo is what they would have wanted but it just seemed like the right thing to do.