(This post was originally published on the Texas Health Moms blog on May 15, 2012.)

By Melanie Medina

On May 12, 2012, Herbert Marx turned 78 years old. Had it not been for his mother, Selma Marx, Herbert may not have lived past the age of 6.

That’s how old he was when German soldiers came to the house in Karlsruhe, Germany, where he lived with his mother, three aunts and grandmother. The soldiers took them from their home with only the clothes that they were wearing and packed them into a dark train compartment with other Jews.

He had always wanted to go on a train ride. Herbert stood there, squeezed among adults who were crying.

For two days, they stood in their own excrement while the train headed southwest through France. They were finally deposited at Gurs Internment Camp near the border between France and Spain – more than 850 miles from home. Herbert doesn’t remember many details of the train ride.

“All I knew was that I was held tightly by the hand by my mother,” Mr. Marx told me in a heavy German accent.

At the camp, he ran around with the five or six other children who were there. When trucks brought in food from outside the camp, the children would stand by the side of the vehicle and extend their arms to the soldiers and wait for baguettes. The children would take the bread back to their barracks, where it would be broken up and shared among the prisoners.

He doesn’t remember being beaten or whipped, although he did see a lot of other people get hurt, he said. He doesn’t remember whether his mother was forced to do hard labor. He does remember scrounging through trash cans outside the mess hall where the German soldiers ate, digging for anything that looked like food. He would take whatever he could find to his mother.

Other than this, Herbert doesn’t remember much about six months he spent in the concentration camp. Except that he slept on the same wooden bunk with his mother.

“A lot of times she held me in her arms,” he said.

One day, Selma told her son, “The nice German soldiers are going to take you for a ride.” He was hidden on a truck among the soldiers, who dropped him off at a Catholic orphanage in Toulouse, France. He never saw his mother again.

—

As a 34-year-old woman who was born and raised in what is arguably the most prosperous country in the most prosperous time in history—who’s never seen war outside the comfort of a movie theater—I have no frame of reference to help me comprehend what this must have been like.

But I am a mother. And I know what it feels like to hold my 2-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter while they sleep.

Nearly every morning when I take them out of their beds to get ready for the day, I let them sleep on me for a few minutes. These are the most sacred minutes of my day.

I carry my groggy girl down the stairs and smell her sweet morning breath as she breathes on my neck. I hold her for a while, then lay her on the couch while I get my son out of his baby bed.

I hold him with his arms around my neck and legs around my waist. I sit with them in our dark living room before the sun comes up, wishing I could stay there with them on the couch and hold them forever, because I know that faster than I can blink my eyes, I’ll have to let them go.

—

And then I think of Selma. I cannot speak for her or even fully tell her story. Herbert doesn’t remember how tall she was or the color of her eyes. He believes she was a cook at the Jewish kindergarten he attended, but he’s not certain.

When they were together in the concentration camp, I imagine that Selma’s only source of comfort in that horrifying place was the rise and fall of her son’s chest against hers as she held him in the bunk they shared.

I try to imagine what she must have been thinking, knowing that at his young age, she was the only one who could protect him (Herbert’s father, a gentile, was not married to Selma and did not live with them). And knowing, too, that the only way he would be able to grow up would be by her sacrificing her desire to cling to him and let him go. And not just let him go, but send him away.

Herbert spent four years at the Catholic orphanage in Toulouse, France, before he had to be sent away again – to escape from German soldiers looking for any Jewish (circumcised) children. He spent some time in a Jewish orphanage in Switzerland before the Red Cross relocated him with an aunt and uncle in New Jersey.

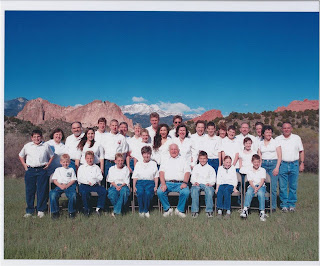

He learned English and graduated from high school. He became a citizen while serving in the U.S. Army (occupying Germany). He earned a bachelor’s degree in business. He married a Catholic woman, Ida, with whom he had seven children. “The Magnificent Seven,” they called them.

He now has 15 grandchildren and one great grandchild. He referees soccer games – soccer is his passion – near his home in Denver, Colorado. He works out at a nearby gym and travels with his new wife (Ida died of ovarian cancer several years ago) to attend his grandchildren’s special events. In 2011, Herbert got to see one of his grandsons walk across the stage to get his high school diploma. The young man just finished his freshman year at the University of Colorado, where he earned a 10-year scholarship that will take him all the way through medical school.

I asked Herbert if, when he looks at how well his family is doing now, he ever thinks about the sacrifices his mother made for his freedom.

“I think about that I wish the mother would have seen what had become of me. When I say me, I mean the family.”

I believe that she sees.

Herbert says that despite everything that happened to his mother (relatives told him that she was gassed at Auschwitz), he still believes that love prevails over hate.

Selma’s family is living, breathing proof that this must be true.

Melanie Medina is a senior communications specialist at Texas Health Resources, where Edward Marx, the youngest of The Magnificent Seven, was Chief Information Officer.