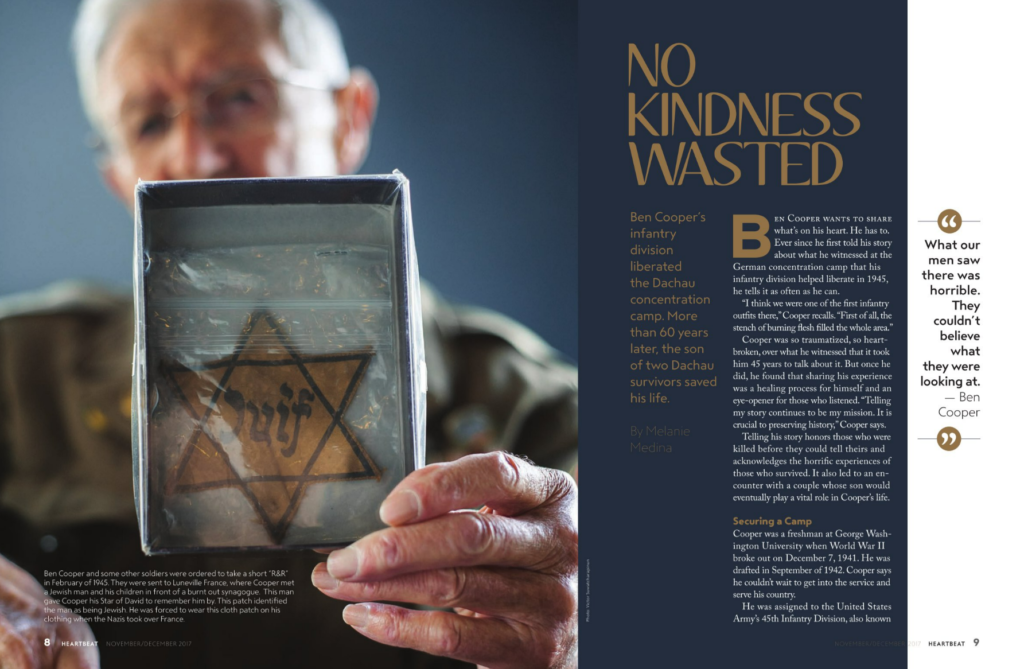

No Kindness Wasted

Ben Cooper’s infantry division liberated Dachau. More than 60 years later, the son of Dachau survivors repaired his heart.

By Melanie Medina

This article was originally published in Heartbeat Magazine, Nov./Dec. 2017

Ben Cooper wants to share what’s on his heart. He has to. Ever since he first told his story about what he witnessed at the German concentration camp that his infantry division helped liberate in 1945, he tells it as often as he can.

“I think we were one of the first infantry outfits there,” Cooper recalls. “First of all, the stench of burning flesh filled the whole area.”

Cooper was so traumatized, so heartbroken, over what he witnessed that it took him 45 years to talk about it. But once he did, he found that sharing his experience was a healing process for himself and an eye-opener for those who listened.“Telling my story continues to be my mission. It is crucial to preserving history,” Cooper says.

Telling his story honors those who were killed before they could tell theirs and acknowledges the horrific experiences of those who survived. It also led to an encounter with a couple whose son would eventually play a vital role in Cooper’s life.

Securing a Camp

Cooper was a freshman at George Washington University when World War II broke out on December 7, 1941. He was drafted in September of 1942. Cooper says he couldn’t wait to get into the service and serve his country.

He was assigned to the United States Army’s 45th Infantry Division, also known as the Thunderbird Division, where he was given the job of combat medic. The division faced combat in France, Italy and Germany. In late April of 1945, as the war was nearing its end, Cooper learned that his division had received orders to secure a camp.

“We didn’t know anything about the camp. We were just told not to let anyone in or out,” Cooper says.

The camp, located in Southern Germany, was called Dachau. It covered an area of three square miles and was surrounded by barbed wire. Approximately 200,000 people suffered and died at the camp between 1933 and 1945.

“General Eisenhower ordered as many troops [as possible] to go back to the concentration camps to be a witness,” Cooper says. What he witnessed was virtually unspeakable.

“As we got closer, the air was permeated by burning flesh,” Cooper says. “We thought, ‘What the hell is going on here?’” As Cooper entered the camp, he saw a sign over the entrance: Arbeit Macht Frei. Work Sets You Free. Inside were tens of thousands of prisoners, including Jews and others of various nationalities.

“We were allowed to go into a large, open field, but not allowed to go into other parts of the camp because of the prevalence of typhus and dysentery. Those survivors who were able to walk could come and meet us,” Cooper says. He recalls hundreds of survivors coming up to him and his fellow troops.

“I couldn’t tell men from women. It was impossible. If they weighed 60 pounds or 70, it was a lot. at traumatized me, my buddies too. They came up to us; they hugged us. They gave us names of people they knew in the United States or elsewhere. They were just so happy to see us, you know? It was unbelievable. And we were just traumatized.”

On April 29, 1945, American soldiers liberated approximately 30,000 people who had been interned at Dachau. Days after that, Cooper’s division helped capture Munich, Germany.

After the European war ended on May 8, 1945, Cooper’s division was sent to France, where they waited to be shipped to the Pacific theatre to fight the Japanese. On August 15, 1945, the war in the Pacific ended, before Cooper and his division were sent there. Eventually, he was discharged from the military and returned home to his wife, whom he had married just months before his deployment.

Lives Intertwined

For years Cooper didn’t tell his wife or children what he saw at Dachau. He didn’t tell anyone. He couldn’t.

“I had it hidden here,” Cooper says. “And it bothered me. It just, like, festered there all the time. And I couldn’t talk to anybody about it. There was no one to talk to, you know. That’s why I didn’t talk for 45 years.

“But now I do. Now I want people to know it happened.”

He first told his story to a group of students in 1990. Since then, he’s told it countless times — to high schools, colleges, civic groups and to historians at the Veteran’s History Project.

In 1996, Cooper attended an annual Holocaust memorial service at the Connecticut State Capitol. He wore a pair of khakis with his Eisenhower jacket, which was designed by General Eisenhower and given to many soldiers at the end of the war. He also wore a bolo tie with his division’s insignia: a bright yellow thunderbird on a red background.

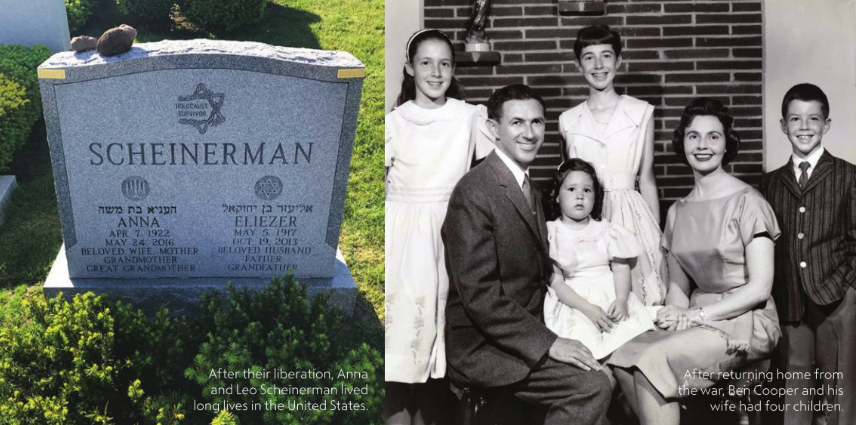

A man named Eliezer “Leo” Scheinerman approached Cooper at the event.

“I remember that,” Scheinerman said, gesturing to Cooper’s thunderbird tie.

“Why?” Cooper asked. “Were you at Dachau?”

“I was there with my wife,” the man answered.

Leo and his wife, Anna, were among those liberated from Dachau. Fifty years later, they recognized the insignia worn by the soldiers who helped free them.

Cooper and his wife became close friends with the Scheinermans. They learned about each other’s lives after the war and shared stories about their children.

After their liberation, the Scheinermans lived in Italy for four years. They had their first child there. They immigrated to the U.S. in 1949 and settled in Connecticut, where they had two more children. Leo and Anna put all three of their children through college, and put their youngest, Jacob, through medical school.

Mended Hearts Lore

In 2006, Cooper learned that he needed open heart surgery. He asked that Jacob Scheinerman, who was by this time a prominent heart surgeon in Connecticut, perform the surgery.

“Now is that something?” Cooper says. “Just to show you Hitler was killing millions of people. And here this couple, who survived Dachau, had a son who saved my life.”

The surgery that fixed his heart — and the surgeon who did it — have been part of Cooper’s story for 11 years and counting. “What goes around comes around,” he says.

“It was meant to be that, number one, [Cooper] would see my parents some 50 years later and that they would be able to share that together,” says Jacob Scheinerman, M.D. “And then that he would need open heart surgery and would come to me.”

One of the first people to hear the newest chapter in Cooper’s story was the Mended Hearts volunteer who visited Cooper after the surgery. His name is Rocky Goodwin. And Goodwin, of course, shares Cooper’s story far and wide.

The Scheinermans’ Legacy

Leo and Anna Scheinerman went to great lengths not to talk about Dachau in front of their children. But still, their children knew.

“When they would try to hide things from us, they would speak in Yiddish,” Dr. Scheinerman says. “And little by little I learned to understand Yiddish fluently.

I couldn’t speak it, but I could understand everything they were saying, and that’s how I really learned about all the horrific things that they’d experienced.”

He learned that his father lost eight brothers and sisters in the Holocaust, and his mother lost both of her parents.

“I was the only kid growing up who didn’t have grandparents,” Dr. Schein- erman says.

The Jewish high holy days also gave Dr. Scheinerman and his siblings a glimpse into Leo and Anna’s pain. Because Leo and Anna did not know when their parents had died, a rabbi advised them to observe the anniversary of their death at Yom Kippur. “ at was a difficult time that I could see for them on an annual basis, and that I’ll never forget,” he says.

Dr. Scheinerman doesn’t often talk about what happened to his parents at Dachau because he knows how hard they tried to protect him and his brothers from it. He does not see movies or documentaries about the Holocaust. It is too painful for him to imagine what his parents were put through.

He’d rather think about the positive.

“They worked day and night to support a family,” Dr. Scheinerman says. “My father was a man of small habitus. He was maybe five-seven, 135 pounds, and he did everything from unloading trucks to sweeping floors. And even when eventually they saved enough money to have his own business, he worked almost seven days a week to provide for his family. They put us all through college, and for me, medical school.”

Leo and Anna’s three sons gave them six grandchildren. “And my mother got to see one great-grandchild before she passed,” Dr. Scheinerman says.

Dr. Scheinerman knows his parents’ story — and Ben Cooper’s — has to be shared. “There just aren’t that many people still alive who can talk about their experiences of what went on,” he says.

Maybe Peace Will Catch On

“I don’t care what your religion is or what your background is or your culture,” Cooper says. “You know we all belong to the same race. The human race.”

With wars being waged over religious ideologies, and hatred thrown back and forth between political parties, Cooper hopes that some people, especially younger generations, will take his message to heart.

He tells the students he speaks to, “If you want to feel good and make someone else feel even better — just think of this — no act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted. Think of that. Try to do it every day.

“Whether you open a door for someone, help someone across the street. And if you see someone in danger or who needs help, as long as you don’t get into harm’s way yourself, try to help them. Do something to help them out.

“Maybe in time it will promote peace and bring back peace to the world and respect for each other.”

###

The story behind this story. I’ll never forget writing this one.

I was pulling into the parking lot at Jake’s (a bar in Flower Mound) to have a beer with my husband when my phone rang. I almost didn’t answer it. I’m glad I did because it was a source who I’d been trying to connect with for weeks—Ben Cooper, a 90-something WWII veteran and open-heart surgery patient. He was calling to tell me about the surgeon who performed his bypass operation.

Mr. Cooper’s infantry unit was there at Dachau when the camp was liberated, and among those set free were the surgeon’s parents.

Mr. Cooper told me that President Eisenhower sent his unit, the 45th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, not just to help liberate it, but to bear witness to what was happening there.

As I bore witness to Mr. Cooper’s story, I couldn’t scramble fast enough to find something to take down all he was telling me. He’s an older gentleman, and I didn’t want to interrupt him by asking him to wait for me to hit “record” on my iPhone. I dug through my glove compartment box, found the owner’s manual to my 2016 Ford Explorer, and thank God, found a pen. I wrote as fast as I could to tell Mr. Cooper’s story.